Cell Phone Forensics

If you are looking for answers to questions only the inner-workings of a phone can answer, our investigators can help.

Mobile device forensics accounts for a large portion of the work Gillware Digital Forensics does. Among our mobile device forensics cases, cell phones are the most common type of device submitted for analysis. Cell phone forensics can be a complicated field, but Gillware’s forensic experts have years of experience and advanced training to ensure the best possible results of each forensic case.

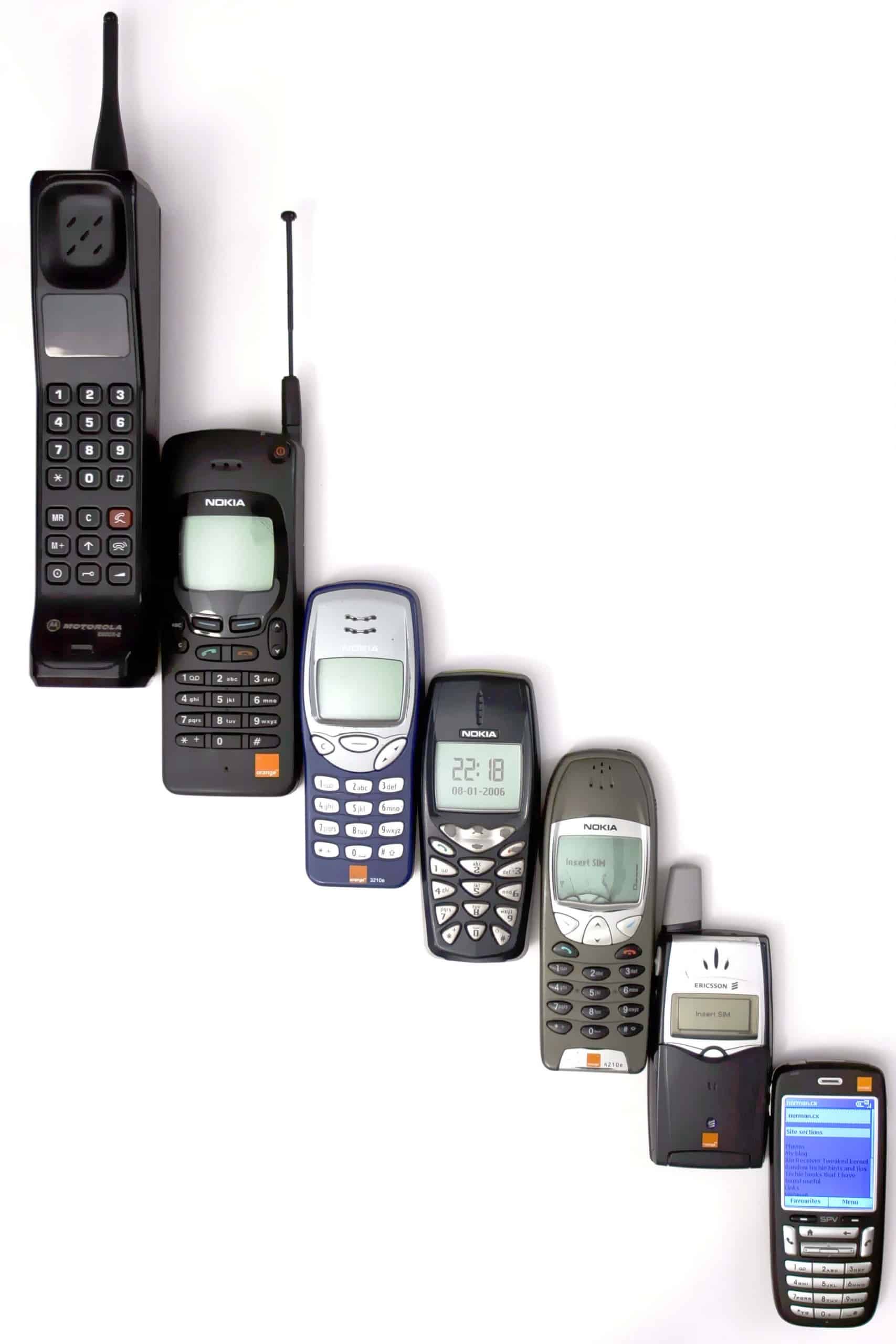

History of Cell Phones

Although it may seem to some to be a newly emerging field, cell phone forensics has been around for well over 10 years. When most people think of cell phone forensics, the data stored on smartphones comes to mind. However, cell phone forensics was already being used by investigators long before the proliferation of smartphones.

The term “cellular ” refers to the network of towers that provide service to devices. The reach of each tower is its own “cell”, and by having multiple towers in an area, each with their own cell, an area can have full service coverage.

The first true handheld mobile phone was produced in 1973 by Motorola. Prior to this, mobile phones had existed in cars or other vehicles (including donkeys in the military!), but this was the first device to be truly mobile. From there, multiple generations of cell phones have been developed, leading up to modern devices.

1G or first generation cell phones and the associated network technology were analog, first deployed in Japan in 1979. They reached the US by 1983 after over a decade of development. The first cell phones had a talk time of just 35 minutes and took 10 hours to charge. Even though they had terrible battery life, low talk time and were very heavy, demand was still high with thousands on waiting lists.

2G or second generation cell phones and network technologies were digital, first introduced in the 1990s. These phones began to introduce features that look more like phones we’re accustomed to seeing today, including prepaid mobile phones, SMS or text messaging, downloadable content (starting with the ever-popular ring tone), mobile payments and eventually full Internet service. This generation also saw the invention of the first smartphone. The IBM Simon introduced features that seem commonplace to us now, but at the time were revolutionary for such a small piece of technology. Simon was a phone, pager, fax machine and Personal Digital Assistant (PDA) combined. Tools included a calendar, address book, clock, calculator, note pad, email and touch screen with QWERTY keyboard and stylus.

3G or third generation cell phones and network technologies were born from the fast growing demand for data usage, such as Internet browsing on a phone, and greater data speeds. This was accomplished by moving from circuit switching to packet switching networks for data transmission. The standardization process of cell phone performance became more of a focus over technology, pushing manufacturers to develop better devices and networks. The first pre-commercial trial 3G network was launched in Japan in 2001. Features introduced during this time began to advance rapidly, including streaming capabilities for radio or TV, quality Internet access, dongles to connect to computers, Wi-Fi capabilities and more. This generation also saw the introduction of data-aware devices like 3G-capable laptops called “netbooks”, as well as other devices with embedded wireless Internet like the Amazon Kindle or the Apple iPad. In 2007 Apple launched the iPhone and thus began the proliferation of smartphones.

Beginning in 2009, it was determined that 3G networks would no longer be able to keep up with the demands that users put on them with bandwidth-heavy activities such as streaming media. 4G or fourth generation cell phones began using native IP networks and eliminated circuit switching, treating voice calls like any other type of streaming media by using packet switching over Internet, LAN or WAN networks through VoIP. The devices we most commonly think of as smartphones today are either 3G or 4G smartphones. Many 3G phones are still in use, as 4G networks have not been established in many places.

One other type of cell phone to note is the satellite mobile phone, which connects to Earth-orbiting satellites rather than land-based cell towers. This is advantageous to users in remote areas where cell network coverage may not be available.

Why Cell Phone Forensics?

The number of cell phones in the United States exceeds the population, which speaks to not only how common the devices have become, but also to the evidentiary potential of cell phones in an investigation. As mobile technology continues to advance and the user base continues to expand, cell phone forensics becomes more and more important to an investigation. Cell phones are tiny computers that people have with them nearly constantly, making them an integrated part of their daily lives and holding more data than ever before.

Cell phones, especially smartphones, contain a myriad of information that could be valuable evidence, including the obvious such as call logs, contacts, text messages, pictures, videos, sound recordings and Internet browsing data. Additionally, less visible data that a cell phone collects beneath the surface can sometimes be just as, if not more valuable. Data such as passwords or passcodes, GPS data, app data, dictionary content, system files, usage logs or data deleted from the phone by the user that is still being stored on the device can become key to answering important questions.

There are a number of different applications for cell phone forensics. Gillware Digital Forensics has experience working with a variety of different customers with different needs and can adapt their process based on your needs. Law enforcement officers and detectives can benefit from cell phone forensic data for investigation of criminal cases or traffic incidents. Law firms looking to use cell phone data for court cases can also benefit from cell phone forensics. Corporations investigating employee data theft of misconduct on company owned devices could also use cell phone forensics services to obtain the information they need.

How Cell Phone Forensics Works

There can be a number of barriers and challenges to cell phone forensic examinations. Phones are often locked with a passcode, which can prevent an investigator from being able to access the data. Most phones come with an optional security feature that deletes data on a phone if an incorrect passcode is entered too many times, making “brute force” attempts to unlock the phone by simply inputting every possible combination of passcodes potentially risky. In other cases, a user who knows they are being investigated may attempt to delete or remotely wipe data in an attempt to hide or destroy evidence.

These cases are challenging enough, but on top of these potential barriers, some phones that undergo cell phone forensics examinations are also physically damaged, often intentionally. Users that want to hide evidence often go a step further than simply deleting data and attempt to destroy devices by smashing them, throwing them in a body of water or attempting to burn them. Sometimes these physically damaged phones aren’t submitted for examination because it is assumed that they are destroyed beyond recovery. However, forensics investigators have experience with cell phone forensics from water damaged phones, fire damaged or burned phones, and smashed, cracked, broken or shattered phones and have had success acquiring data from such devices.

Gillware uses a number of software tools to acquire data from cell phones, such as Cellebrite and other mobile device forensics tools. These tools support for many different models of smartphones, and can often allow investigators to access phones that are locked with passcodes. In some cases, these programs can extract data and give analysts a look into the inner workings of the phone. However, forensic programs cannot always perform these extractions, which is one of the major challenges in mobile device forensics.

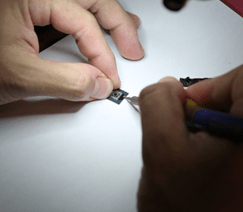

When less common models of devices are not supported (or are only partially supported) by forensic toolkits, physical data extraction may be necessary. Physical extraction methods, including JTAG and Chip Off, are employed when software tools do not support a phone, or the phone is too severely damaged to work with. When investigators acquire raw data from JTAG or Chip Off, it’s like spilling all the pieces of a jigsaw puzzle out of the box. The trick is then figuring out how all the puzzle pieces fit together into recognizable data. Sometimes forensic tools can help with this, but other times investigators need to reassemble the data on their own.

Have questions about cell phone forensics? Or looking for answers from within cell phone files?